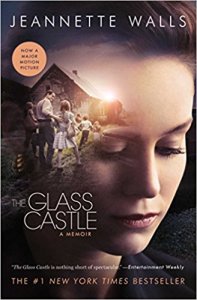

By Jeannette Walls

By Jeannette Walls

Scribner, ISBN: 978-1501171581

Paperback, 320 pages. ©2017 (Revised Edition)

When she is three years old, Jeannette Walls catches fire. Standing on a chair in a tutu at the gas stove, cooking hot dogs, she feels the heat as flames kindle in her puffy pink skirt and rage up her side. She freezes in fear before she begins to scream. Her mother, Rose Mary, rushes in, wraps her in a blanket and takes her to the neighbor’s, who drives them to the hospital. Nurses and doctors treat Jeannette’s severe burns and whisper how she’s lucky to be alive. When she’s better, and able to answer their questions, they ask her about her other scars, and how she got burned in the first place. “My mom says I’m mature for my age,” she explains. “She lets me cook by myself all the time.”

After weeks in the hospital Jeannette’s father, Rex, decides he’s had enough of the doctors’ demands and questions. He appears at the hospital in the dead of night and bundles his little girl out, running just ahead of hospital security and the law. This, we readers learn, is “the Rex Walls skedaddle,” a retreat that occurs again and again throughout the book whenever the family—or Rex in particular—gets into trouble.

Thus begins Glass Castle, a story about life on the move with deeply dysfunctional parents who can’t hold down a job and who make big promises that never come to fruition. Rex is an alcoholic and a gambler who will charm, connive, sneak, bully, lie and cheat his way to a dollar so he can have another drink. Rose Mary is an aspiring artist who wants nothing more than to paint the world she sees through her rose-colored glasses. Throughout the story, she manages to salvage her art supplies and numerous canvasses even when the children can’t manage to keep a change of clothes or a basket of food. Neither parent is above putting their children on the line to get what they, the parents, want.

The burn is merely the first in a long line of hair-raising experiences Jeannette and her siblings endure: like the time Rex repeatedly throws Jeannette into the deep end of a hot springs where some animals are known to boil alive just so she will learn to swim; or the time Jeannette falls out the back door of their car on a bumpy ride through the Southwest desert territory and it takes her father hours to realize she’s gone; or the time Jeannette’s older sister almost follows in Jeannette’s footsteps by exploding the gas line in their funky kitchen on the faulty gas line. Once, Rex convinces Jeannette to dress up and distract his opponent at pool so Rex can win a big haul. When Jennette is molested and nearly raped in the ordeal, he shrugs and says “I knew you could handle it. Just like when I threw you in that pool. I knew you’d swim.”

For the mother, Rose Mary, perspective is everything. A life on the run, living hand-to-mouth in challenging circumstances, is a grand adventure. For many long years, the children are persuaded to believe that going without food for days at a time is a good way to “toughen up.” Living in the open desert with no roof over one’s head is “exhilarating.” Bathing or brushing one’s teeth is overrated, as is combing one’s hair. Luxuries such as indoor plumbing (or even outdoor toilets that stay sanitary and usable), or roofs that don’t leak, or floorboards that don’t collapse beneath one’s feet, are negotiable. Rose Mary’s responses to Jeannette’s complaints on any of these things range from “It could be worse” to “Why do I always have to be the one to fix things? If you want money, get your own job.”

Rex, when he isn’t gone for days at a time, plots through the whole book to build a grand house he calls the Glass Castle, even going so far as to draw up the plans and stake out the foundation—though he never gets beyond that point. He is a man with big dreams that always disappear into a haze of booze and rage.

I read page after page with my mouth agape, shaking my head in bewilderment, and yet I know there are plenty of people in this country alone (not to mention citizens of other, less prosperous nations) who live like this. It’s hard to pick one scene or recounted memory that stands out more than others, but if I had to select just one, it would be the time Jeannette tries to make a sandwich from the remains of a week-old, unrefrigerated, canned ham only to find it squirming with maggots. When she tells her mother about this, Rose Mary shrugs and says “Cut away the wormy bits. The rest is fine.”

Glass Castle is not an easy read, but I believe it is an essential one. Walls has pulled away our blinders to the kind of poverty and dysfunction she survived and revealed that it isn’t a simple matter of laziness or lack of motivation that puts a parent into such situations. Roots that give rise to such a life go deep, and are sometimes unfathomable to anyone who hasn’t lived it themselves. She also gives that history a bit of a shine. I can see how, as a child, she would see their skedaddles as an adventure. And it’s clear that Rex and Rose Mary were brilliant, and that they passed that education on to their children in the form of literary knowledge, mathematics, engineering, astronomy, history, so many topics kids their ages usually never learn. By the time they are actually enrolled in schools, the Walls children are ahead of their peers in almost every subject (socialization notwithstanding).

There is so much more I could say, but it boils down to the fact that I can’t recommend this book enough. It’s one of the best memoirs I’ve ever read, bar none.

I hear stories like this from my patients sometimes.

Laura, I can imagine. I’m sure some stand out more than others, yes?